Internationalisation and ethics

This article was first published on our School Collaboration website in Norwegian.

The students at Ullern Upper Secondary School faced great philosophical questions in the classroom, when Øyvind Kongstun Arnesen visited in April. This turned into an exciting and relevant session about strategy, ethical distribution of vaccines and many other things.

On Tuesday, the 20th of April, half of the students of entrepreneurship are present in the classroom, while the rest follow the session via video link. This is “the new normal” as education is adapted to the health regulations during a pandemic.

The subject today is internationalisation and ethics. Øyvind Kongstun Arnesen has been brought in as lecturer to start the discussion and share his experiences.

Kongstun Arnesen has long experience as doctor, medical director in several global pharmaceutical companies, former CEO of the vaccine company Ultimovacs and, chairman and member of the board in several companies.

The students heard him speak about raising funds earlier during the school year. You can read more about the lecture in this article: Fundraising on the curriculum

“Born global”

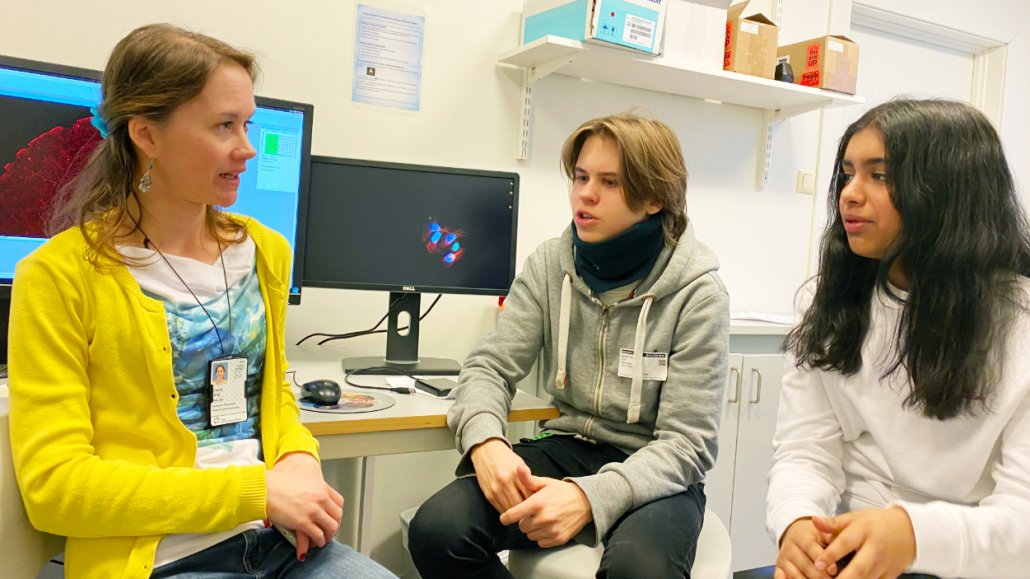

Øyvind Kongstun Arnesen inspired the students with his reflections on and experiences of internationalisation and ethics in the pharmaceutical industry. Photo: Elisabeth Kirkeng Andersen

Kongstun Arnesen tells the students that Norwegian biotech companies, such as Ultimovacs that he led for 10 years, are known as “born global”. It means that going international is not a matter up for discussion, it is a necessity.

“The Norwegian market is so small that it isn’t an option to develop a treatment only to be used in Norway. The cancer vaccine from Ultimovacs needs to be developed abroad in clinical studies, and the same goes for the approval of it, so the company has a strong international presence from day one,” says Kongstun Arnesen.

An important strategic choice for companies that develop medicines is whether to go all the way to sell it on the market on their own or to licence the product to a big pharmaceutical company.

“This isn’t only a choice that biotech companies must make. My neighbour, for instance, sells hats. They are building a brand and the strategy is to build a brand large enough that the company will be attractive for an acquisition in the future. Ultimovacs has almost the same strategy. We have developed, and the company still develops, a product good enough that it is attractive for licencing,” says Kongstun Arnesen.

The marketing of the company is an important element to succeed with a strategy for acquisition or licencing. Ultimovacs needs to reach international pharmaceutical companies, and not the general public. The pharmaceutical companies are potential collaboration partners and clients.

One of the students wonders which collaboration partners Ultimovacs already has.

“There are three larger pharmaceutical companies we work with: Bristol Myers-Squibb, Merck and Astra Zeneca,” says Kongstun Arnesen.

At the sound of the name Astra Zeneca, the questions from students come flooding and they ask about corona vaccines and the distribution of vaccines in the world today.

Corona vaccines and ethics

Student: “Can for example the corona vaccine from Astra Zeneca create mistrust towards the cancer vaccine that Ultimovacs is developing?”

Kongstun Arnesen: “No, I don’t think so. Cancer vaccines are completely different. It is a vaccine that removes serious disease. This is something separate from the vaccination against the corona virus to prevent serious disease. Also, very few people get the side effects from the Astra Zeneca vaccine. You could ask how many more would die from corona if they are not vaccinated with this vaccine, but we don’t hear about this in the media.”

Student: “I have heard talk that EU don’t want to licence the corona vaccines to Africa. Is this right and can they decide that?

Kongstun Arnesen: “That is a good question. I will get back to the question of distributing vaccines globally, but first I want to go back a bit in history.”

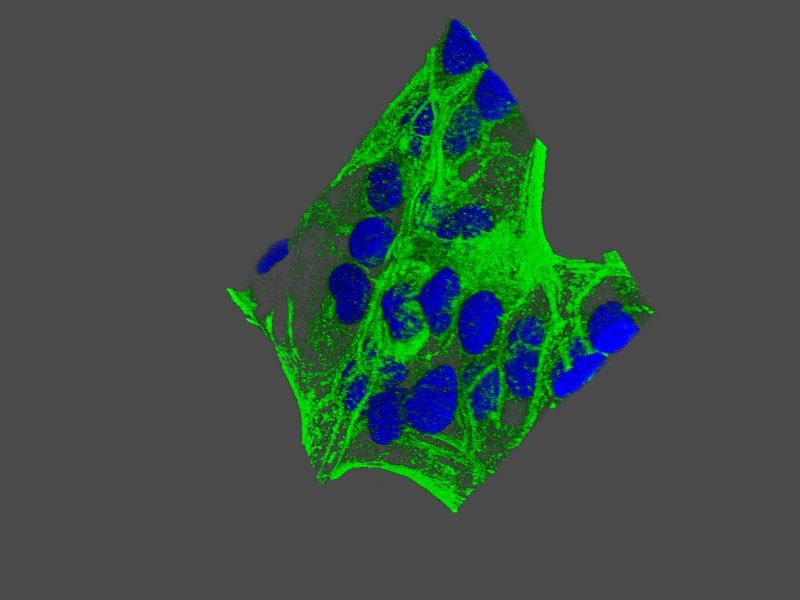

In the series It’s a sin from 2020, the HIV/AIDS epidemic is portrayed through a group of friends in London.

“You may not remember the HIV/AIDS epidemic. We first discovered the disease in homosexual men, and then in other people too. They died of immune deficiency, and there was a race to produce medicines against this. I was a general practitioner in Lofoten when this was at its worst in Norway. The authorities were working with a ‘worst case scenario’ in which 30% of the Norwegian population would die. When the medicines came, it was like turning off a switch. The patients who had been admitted to hospital before there were medicines, were admitted to die. When the first doses came, the patients became well and were discharged.

“The question was: How can we distribute the medicines over the world? HIV/AIDS was a much greater problem in Africa – in other words, in countries that could not afford the medicines. The pharma companies started giving away licences for free or at very large discounts to a factory in India that produced vaccines, which were then sold to poor countries. This made the medicines available to many more people.

“Another way of doing this is, for example, through the organisation COVAX. This is a collaboration between wealthy countries that buy vaccines for poor countries.

“A challenge is that the companies that develop new vaccines or medicines need to have an economic incentive to do this, they cannot develop medicines for free. Israel negotiated by themselves with the pharmaceutical industry to buy vaccines against corona, but they have also paid five times the price as many other countries, and not everyone can afford this.

“If you ask me, the distribution of pharmaceuticals in the world today is completely unethical and, in many ways, characterised by the pharmaceutical industry being extortioners. They develop medicines that can save lives and can set a high price. At the same time, they could make a choice and say to the owners or investors that they wish to set a reasonable price for the medicine, and not to have maximal profit. We had this discussion with our owners in Ultimovacs and it made me happy to see that the owners were positive to us not setting the maximum possible price.”

After a while, the questions multiplied, and a lively discussion ensued. We will not repeat everything here, that would make the article too long, but we will include one last question.

Student: “Why don’t we produce vaccines in Norway?”

Kongstun Arnesen: “We don’t have a vaccine factory in Norway. We had one about seven or eight years ago at the Institute of Public Health. When it was decided to close down the factory, an international company wished to acquire parts of the equipment and set up their own production of vaccines here. The Norwegian authorities became too demanding in the negotiations and the company chose to invest in building a factory in a different country instead. Norway lost the negotiations because they asked for a too high price, and then one thing led to another.”